When you type a URL into your browser and press Enter, an incredible sequence of events happens in milliseconds.

Understanding how the web works is fundamental to becoming a proficient web developer. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore client-server architecture, HTTP/HTTPS protocols, the request-response cycle, status codes, and headers.

What is the Web?

The World Wide Web (WWW) is a system of interconnected documents and resources accessible through the Internet. While often used interchangeably, the internet and the web are different:

- The Internet: The physical infrastructure of networks, cables, routers, and protocols that connect computers worldwide

- The Web: An application that runs on top of the Internet, allowing us to access web pages, images, videos, and other resources through browsers

Think of the internet as the road system, and the web as the cars traveling on those roads.

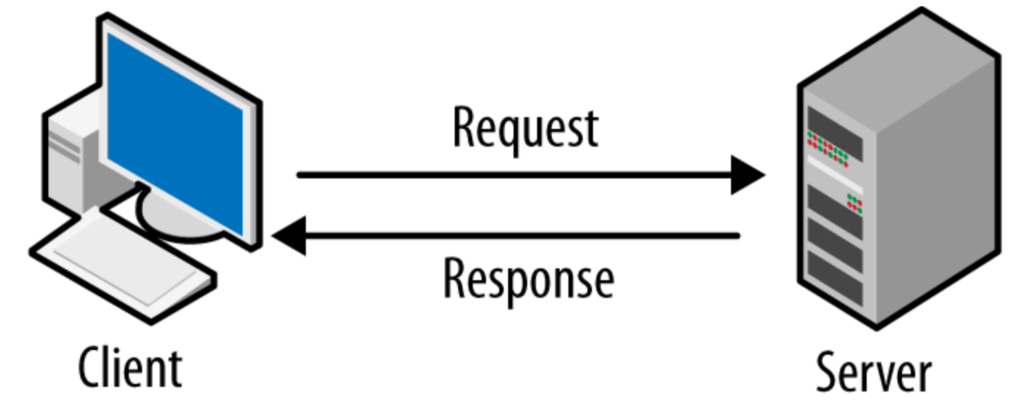

Client-Server Architecture: The Foundation of the Web

The web operates on a client-server model, one of the most fundamental concepts in web development.

What is a Client?

A client is any device or application that requests resources from a server. Common examples include:

Examples include:

- Web browsers (Chrome, Firefox, Safari, Edge)

- Mobile applications

- Command-line tools like cURL

- IoT devices

When you open your browser and navigate to a website, your browser acts as the client, requesting information from remote servers.

What is a Server?

A server is a powerful computer that stores and serves web resources to clients. Servers run specialized software designed to:

- Listen for incoming requests

- Process those requests

- Send back appropriate responses

- Handle multiple requests simultaneously

Servers can host websites, APIs, databases, files, and more. Popular web server software includes Apache, Nginx, and Node.js.

How Clients and Servers Communicate

The communication between clients and servers follows a request-response pattern:

- Client sends a request: “I want to see the homepage of example.com”

- Server processes the request: Finds the requested resource

- Server sends a response: Returns the HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and other files

- Client renders the response: Browser displays the webpage

This happens constantly as you browse the web, often multiple times for a single webpage. (Refer the image attached above)

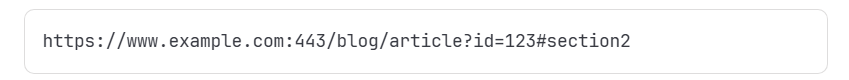

Understanding URLs: Web Addresses

Before diving into HTTP, let’s understand URLs (Uniform Resource Locators), the addresses we use to locate resources on the web.

A URL has several components:

Breaking this down:

- Protocol (

https://): How to communicate with the server = Tells the browser which rules to use when talking to the server.http→ plain text (not secure)https→ encrypted using TLS (secure)

- Subdomain (

www): A subdivision of the main domain- Used to organize or separate services.

- Common examples:

www.example.com→ websiteapi.example.com→ APIadmin.example.com→ admin panel

- Domain (

example.com): The human-readable server address- Behind the scenes, DNS converts this to an IP address

- example.com → 93.184.216.34

- Port (

:443): The specific port on the server (this part is usually hidden)- A port identifies which service on the server should handle the request.

- Common ports:

80→ HTTP443→ HTTPS22→ SSH3306→ MySQL

- Path (

/blog/article): The specific resource location on the server or the routes- Tells the server what you want.

- Historically mapped to folders/files.

- In modern apps (Node, Spring, Rails, etc.), it maps to routes/controllers.

- Query String (

?id=123): Additional parameters sent to the server- Additional parameters sent to the server

- Used to send key-value pairs.

- Common uses

- Filtering (

?category=tech) - Pagination (

?page=2) - Search (

?q=wcag) - Identifiers (

?id=123)

- Filtering (

- Fragment (

#section2): A specific section within the page- A specific section within the page

- Used by the browser only

- Not sent to the server

- Typical uses:

- Jump to a section in a page

- Single-Page Apps (Angular/React) routing

- Tabs or anchors

DNS: Translating Domain Names to IP Addresses

Computers don’t understand domain names like “example.com” — they use IP addresses (like 93.184.216.34) to identify each other on the network.

The Domain Name System (DNS) acts as the internet’s phonebook, translating human-readable domain names into IP addresses:

- You type “example.com” in your browser

- Your browser asks a DNS server: “What’s the IP address for example.com?”

- DNS responds: “It’s 93.184.216.34”

- Your browser connects to that IP address

This process is called DNS resolution and happens before any HTTP communication begins.

HTTP: The Protocol of the Web

HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol) is the foundation of data communication on the web. It defines how messages are formatted and transmitted between clients and servers.

Key Characteristics of HTTP

Stateless Protocol: Each request is independent. The server doesn’t remember previous requests from the same client unless we implement additional mechanisms (like cookies or sessions).

Text-Based: HTTP messages are human-readable text, making them easy to debug and understand.

Request-Response Model: Every interaction consists of a request from the client and a response from the server.

HTTP Request Structure

An HTTP request contains several parts:

GET /blog/article HTTP/1.1

Host: www.example.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64)

Accept: text/html,application/json

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9

Connection: keep-alive

Components of an HTTP Request:

- Request Line: Method, path, and HTTP version

- Headers: Metadata about the request

- Body: Data sent with the request (for POST, PUT methods)

HTTP Methods

HTTP defines several methods that indicate the desired action:

- GET: Retrieve data from the server (most common)

- POST: Send data to create a new resource

- PUT: Update an existing resource

- PATCH: Partially update a resource

- DELETE: Remove a resource

- HEAD: Like GET, but only retrieves headers

- OPTIONS: Check what methods are supported

Example scenarios:

- Loading a webpage:

GET /index.html - Submitting a form:

POST /submit-form - Updating profile info:

PUT /user/123 - Deleting a comment:

DELETE /comment/456

HTTP Response Structure

After processing a request, the server sends back a response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Wed, 28 Jan 2026 10:30:00 GMT

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

Content-Length: 1234

Server: Apache/2.4.41

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Example Page</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello, World!</h1>

</body>

</html>

Components of an HTTP Response:

- Status Line: HTTP version, status code, and status message

- Response Headers: Metadata about the response

- Response Body: The actual content (HTML, JSON, image data, etc.)

HTTP Status Codes: Understanding Server Responses

Every HTTP response includes a status code that indicates the result of the request. Status codes are grouped into five categories:

1xx – Informational Responses

These indicate that the request was received and is being processed:

- 100 Continue: The server has received the request headers

- 101 Switching Protocols: Server is switching to a different protocol

You’ll rarely encounter these in everyday web development.

2xx – Successful Responses

The request was successfully received, understood, and accepted:

- 200 OK: Standard successful response

- 201 Created: Resource successfully created (common with POST)

- 204 No Content: Success, but no content to return

- 206 Partial Content: Only part of the resource is returned

3xx – Redirection Messages

Further action is needed to complete the request:

- 301 Moved Permanently: Resource has permanently moved to a new URL

- 302 Found: Temporary redirect to a different URL

- 304 Not Modified: Cached version is still valid

- 307 Temporary Redirect: Like 302, but the method must not change

- 308 Permanent Redirect: Like 301, but the method must not change

4xx – Client Error Responses

The request contains bad syntax or cannot be fulfilled:

- 400 Bad Request: Malformed request syntax

- 401 Unauthorized: Authentication required

- 403 Forbidden: Server understands but refuses to authorize

- 404 Not Found: The requested resource doesn’t exist

- 405 Method Not Allowed: HTTP method not supported for this resource

- 429 Too Many Requests: Rate limiting in effect

5xx – Server Error Responses

The server failed to fulfill a valid request:

- 500 Internal Server Error: Generic server error

- 502 Bad Gateway: Invalid response from upstream server

- 503 Service Unavailable: Server temporarily unavailable

- 504 Gateway Timeout: Upstream server didn’t respond in time

Real-world example:

When you visit a webpage that doesn’t exist, the server returns a 404 status code, and your browser displays a “Page Not Found” message.

HTTP Headers: Metadata for Requests and Responses

HTTP headers provide additional information about the request or response. They’re key-value pairs that control various aspects of the HTTP transaction.

Common Request Headers

Host: Specifies the domain name of the server

Host: www.example.com

User-Agent: Identifies the client software

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36Accept: Specifies what content types the client can process

Accept: text/html,application/jsonAccept-Language: Preferred languages for the response

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9,es;q=0.8Cookie: Sends cookies to the server

Cookie: sessionId=abc123; userId=456Authorization: Contains credentials for authentication

Authorization: Bearer eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9...Referer: The URL of the page that linked to the current request

Referer: https://www.google.com/search?q=web+developmentCommon Response Headers

Content-Type: Specifies the media type of the response body

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Type: image/pngContent-Length: Size of the response body in bytes

Content-Length: 2048Set-Cookie: Sends cookies from server to client

Set-Cookie: sessionId=abc123; HttpOnly; SecureCache-Control: Directives for caching mechanisms

Cache-Control: max-age=3600, public

Cache-Control: no-cache, no-store, must-revalidateLocation: Used in redirects to specify the new URL

Location: https://www.example.com/new-pageServer: Information about the server software

Server: nginx/1.18.0Access-Control-Allow-Origin: CORS header allowing cross-origin requests

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://trusted-site.comHTTPS: Secure HTTP Communication

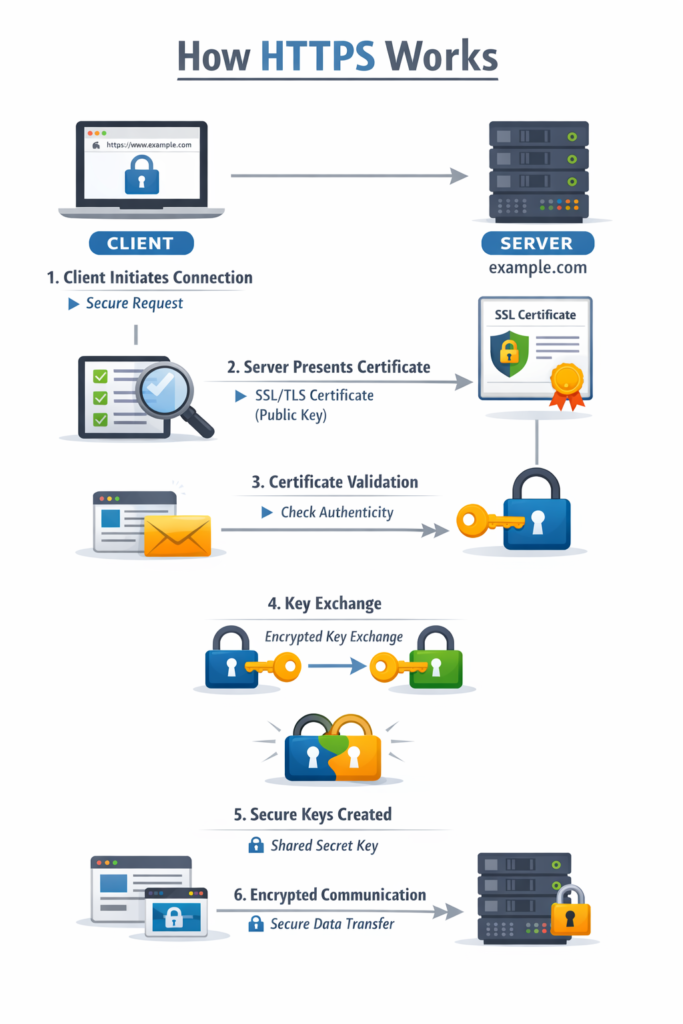

HTTPS (HTTP Secure) is the encrypted version of HTTP. It uses SSL/TLS protocols to encrypt communication between the client and the server.

Why HTTPS Matters

- Security: Prevents eavesdropping and man-in-the-middle attacks

- Privacy: Protects sensitive data like passwords and credit card numbers

- Data Integrity: Ensures data isn’t tampered with during transmission

- Trust: Browsers mark HTTPS sites as secure, building user confidence

- SEO: Google favors HTTPS sites in search rankings

How HTTPS Works

- Client initiates connection: Browser requests a secure connection

- Server presents certificate: Contains server’s public key

- Certificate validation: Browser verifies certificate authenticity

- Key exchange: Client and server establish encryption keys

- Encrypted communication: All data is encrypted using agreed-upon keys

Look for the padlock icon in your browser’s address bar — that indicates an HTTPS connection.

HTTP vs HTTPS

| Feature | HTTP | HTTPS |

|---|---|---|

| Port | 80 | 443 |

| Security | Unencrypted | Encrypted |

| Certificate | Not required | Required |

| Performance | Faster (slightly) | Minimal overhead |

| SEO | Lower ranking | Better ranking |

| Trust | Lower | Higher |

The Complete Request-Response Cycle

Let’s trace what happens when you visit https://www.example.com/blog

Step 1: DNS Resolution

- The browser checks the cache for example.com’s IP address

- If not cached, it queries the DNS server

- DNS returns IP address: 93.184.216.34

Step 2: TCP Connection

- The browser establishes a TCP connection to the server on port 443

- Three-way handshake ensures a reliable connection

Step 3: TLS Handshake (for HTTPS)

- Client and server negotiate encryption

- The server sends the SSL certificate

- Encryption keys are established

Step 4: HTTP Request

GET /blog HTTP/1.1

Host: www.example.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0...

Accept: text/htmlStep 5: Server Processing

- The server receives and parses the request

- Determines the requested resource

- Prepares the response

Step 6: HTTP Response

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

Content-Length: 5420

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>...Step 7: Browser Rendering

- The browser receives HTML

- Parses HTML and discovers additional resources (CSS, JS, images)

- Makes additional requests for these resources

- Renders the complete page

Step 8: Connection

- Connection may stay open (keep-alive) for additional requests

- Or close after the response

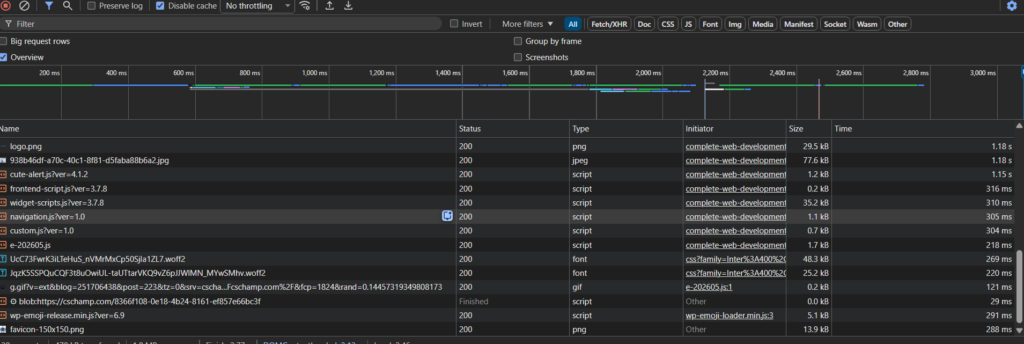

Practical Example: Viewing HTTP Traffic

In Chrome or Firefox:

- Open Developer Tools (F12 or right-click → Inspect)

- Click the “Network” tab

- Refresh the page

- Click on any request to see headers, response, timing, etc.

What you’ll observe:

- Multiple requests for a single webpage

- Different file types (HTML, CSS, JavaScript, images)

- Status codes for each request

- Request and response headers

- Loading times and sizes

This is an invaluable tool for debugging and understanding web communication.

Key Takeaways

Understanding how the web works is essential for every web developer. Here’s what you should remember:

- Client-Server Architecture: Clients request resources, servers provide them

- DNS: Translates domain names to IP addresses

- HTTP Methods: GET retrieves data, POST sends data, PUT updates, DELETE removes

- Status Codes: 2xx success, 3xx redirect, 4xx client error, 5xx server error

- Headers: Provide metadata about requests and responses

- HTTPS: Encrypted version of HTTP for secure communication

- Request-Response Cycle: Every web interaction follows this pattern

Practice Exercise

Open your browser’s Developer Tools and:

- Navigate to any website

- Examine the Network tab

- Identify the HTTP methods used

- Find different status codes

- Inspect request and response headers

This hands-on exploration will solidify your understanding of HTTP communication.

What’s Next?

Now that you understand how the web works at a fundamental level, you’re ready to start building for it. In the next lesson, we’ll set up your development environment with the tools you need to create websites.

Next Lesson: Development Environment Setup – Configure your code editor, browser tools, and create your first web project

One thought on “How the Web Works: Understanding Client-Server Architecture and HTTP Protocol”